Pam Perillo greets me at the door of her trailer, the yaps of a chihuahua named Peewee nearly drowning out our niceties. Perillo had just been looking for something to put on TV to soothe her animals—the territorial dog, two cats named Karla Faye and Tucker, plus a kitten she just rescued—while she leaves for a few hours. I’m driving her from her home in Prairie View, a nearly 9,000-person town at the far edge of the Houston metro, into the city for an event where she’s speaking.

Perillo, 69, is tiny in height and build, with massive blue-green eyes and numerous facial piercings. Tattoos peek out from the sleeves of her pink business-casual blouse. In the car, she brainstorms what to say; she’s been allotted ten minutes to talk about herself. “I don’t really know what to talk about,” she says on the August morning as we start our drive. “I think ten minutes is a long time.”

It’s arguably not long enough for her to scratch the surface of her story. And nowhere near as long as the 40 years she spent in prison, half of that on women’s death row. “I guess I could just say I’m a death row survivor,” she muses.

In 1980, a Harris County jury sentenced a 24-year-old Perillo to prison for capital murder. Along with two others, she’d been arrested for the robbery and murder of two men, Robert Banks and Bob Skeens, in Houston on February 23 of that year. Both Perillo and a man named James “Mike” Briddle received the death penalty, Perillo for Skeens’ murder and Briddle for Banks’. The third person charged, Briddle’s then-wife Linda Fletcher, was ultimately re-indicted for aggravated robbery after prosecutors dropped the capital murder charge against her. She testified against Briddle and Perillo and received five years’ probation.

For 20 years, Perillo waited for the state to kill her, twice receiving scheduled dates before eventually getting stays. Then, in 2000, her fate changed. A federal appeals court found major problems with her trial—including a concerning relationship between Perillo’s attorney and her codefendant Fletcher—enough to invalidate the conviction. Rather than re-try Perillo for a 20-year old crime, the State of Texas offered her a deal: life plus 30 years in prison. In 2019, she was released on parole.

Perillo doesn’t celebrate the fact that she walked free after expecting to be executed. She doesn’t think she’s really any different from other, less-fortunate women; she was guilty of the crime she committed. She has no explanation for why she was spared, except that “God must still have a lot of work to do.” She can even exhibit a kind of guilt, as though she believes her second chance should have gone to someone else—another of those women she met on death row who became perhaps the first stable community Perillo had ever known.

Perillo speaks of her childhood in California as if it were conventional. She doesn’t try to elicit sympathy when she describes the eight foster homes she bounced between after her dad began sexually abusing her when she was nine years old. Her mother was already out of the picture—she’d left the family and died in a car accident about a year prior. Perillo talks favorably about the 19-year-old man she met when she was 13, who taught her “everything” about her body, including how to use tampons and brush her teeth. She was even cordial with her abusive father until he died.

She doesn’t really have a bad word to say about Fletcher, either, except to acknowledge that it hurt when she testified in court that Perillo deserved to die. Perillo could have reduced her own punishment to a life sentence by testifying against Briddle, but she declined. She’s matter-of-fact about why: “I don’t believe in the death penalty, so why would I testify to get him the death penalty?”

About 15 minutes after we leave Perillo’s place, we pull up in front of a house in nearby Magnolia surrounded by livestock pens, where her friend Kylee Lynn lives. She’s tagging along, too, so she can hear Perillo speak. Lynn knows about her friend’s past, and she also admits she doesn’t know where she stands on the death penalty. “I feel like with Pam, I know she’s done her time,” Lynn says after settling into the back seat. “Basically, I was more on the side of, ‘That’s what you get,’ until I met Pam.”

Perillo was born in Iowa, but her family relocated to Southern California when she was a year old. When the State of California took her from her father, the intervention set her on a tour of her adopted home state. She saw idyllic Pasadena, inland West Covina, and the high desert of Lancaster. Of the eight homes she spent time in, she says two were fairly nice.

Three years on, at age 12, she landed at a ranch in the desert north of Los Angeles. She had chronic tonsillitis and was still wetting the bed (the latter being why she was removed from her previous foster home). But the ranch was fun. There were plenty of other kids—some the foster parents’ biological children and others state placements like her. There were pigs and donkeys and cows, and Perillo helped with some of the chores, a rare treat for a girl from South LA.

One night, her foster mom, whom Perillo remembers as a big and comforting woman, asked her why she wasn’t sleeping at night. When Perillo said she was scared that if she fell asleep, she’d wet the bed, “She told me, ‘Honey, we’ll put some plastic on that mattress, and you just pee your heart out if you have to. Don’t worry about it.’ I never peed the bed again.”

She stayed at that home for about eight months before she started getting into trouble at school. Eventually, she ran away—she still isn’t sure why. “I ran from everything. Everything that they tried to help me with: drug programs, foster homes, anything,” she says. “I was just a runner.”

The foster family tried to get her back, but the state refused, placing her in another house in West Covina. That placement didn’t last long before Perillo got into trouble at school. When she was 13, in between foster placements, she met Sammy Perillo.

Sammy, 19, caught her eye while she was hanging out at a popular park in South Gate. With him, she started shooting heroin. She ended up moving in with Sammy and his parents—she went to court to be emancipated and married him in a ceremony in Mexico. “I was like a grown up,” she says. “They were so out of things to do with me.” Every other option was gone, and Sammy felt like a protector.

The two began stealing to support their drug habits. Eventually, he got locked up, and she found out soon after that she was pregnant. She was 16. She quit using heroin and, still living with Sammy’s parents, prepared for her life to shift yet again. “That baby was everything to me. She just changed my whole existence.”

Her daughter, Stephanie, was born February 3, 1973. But Stephanie would never see her first birthday.

The girl died of what was called crib death—now commonly referred to as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome—that June. Perillo remembers the day in flashes. “I can still picture her little body there,” she says. “The little hands were purple.” Perillo spent the next six months in a mental hospital.

Five years later, in her early 20s, she became pregnant again, this time with twins. The father was her drug counselor at a Pasadena treatment program, and he told her he didn’t want to be involved. After Perillo was in a car accident, the boys were born early. They spent a month in a neonatal intensive care unit, with Perillo only able to sit next to the babies without holding them. She called them Baby A and Baby B—what had been written on their incubators—until she eventually decided on the names Joseph and Joel. Joseph survived; Joel died after contracting meningitis.

After that, Perillo worked as a dancer at an LA-area bar and made enough money to support herself and Joseph, but eventually she started using heroin again. About a year later, she met two near-strangers, Briddle and Fletcher, and they decided to rob a customer at the bar. It wasn’t a great plan. The customer knew Perillo.

The three immediately went on the run. Perillo took her son, about a year and a half now, to stay with her dad and stepmom. Then, she flew out to Tucson, Arizona, to join Briddle and Fletcher, who had a plan to hitchhike to Florida.

The trio caught rides with truckers, who introduced Perillo to PCP. She remembers the journey to Houston was “crazy,” as she lost herself in new, powerful highs. With each ride east, she got farther away from everything she had ever cared about.

Perillo and her new friends made it to Houston. They were trying to find a ride near the Astrodome when they first met Robert Banks. He offered them a ride and a place to stay if they helped him move into his new place. It wasn’t too long before they decided to rob him for his money and gun collection—the crime that would determine the next 40 years of Perillo’s life.

She’s forthright about the details. The trio had been on drugs and hadn’t slept for five days. Perillo and Briddle hid in wait while Banks and Skeens, a houseguest, were out grabbing donuts one morning. They separated the men, tying them up in different rooms, and then they strangled both men to death. (There are conflicting accounts of where Fletcher, whose murder charge was dropped, was during the course of the crime, but she denied participating in the killing.)

“I think about this stuff now, you know, and what my victims went through and their families and all of that,” Perillo says. “It just eats my head up sometimes.”

The three fled up to Dallas, then back west to Denver. There, Perillo remembers coming down off the drug binge and thinking about what she’d done. She saw a police car stopped at a light, and she jumped in the back to turn herself in.

She was the first of the three brought to trial for the robbery and murders. She heard of the death penalty for the first time when her attorneys told her Texas was seeking it against her. In California, where she had spent most of her life, the state hadn’t executed anyone since 1967. She didn’t know exactly what to expect. She assumed that they “just killed you right then.”

Punishment, of course, wasn’t nearly so swift. Perillo was sent to death row at the Goree Unit in Huntsville. Just down the road, more than a hundred prisoners sat on the male death row at the time, but Perillo was one of only two condemned women.

Three years after her first trial, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found that there’d been an error during her jury selection, so she went back to the Harris County Jail to await a second trial. While there, life changed fast. She underwent treatment for uterine cancer. She saw her son, now six, for the first time since he was a baby, when he came to Houston from California for her retrial. She started thinking more about God. She couldn’t help but feel like she’d changed since her arrest: “I don’t think I found religion,” she said. “I think I surrendered to it.”

At the end of her 22-month jail stay, a second jury sentenced Perillo to death. She went back to death row, now located at the Mountain View Unit—later renamed Patrick L. O’Daniel—in Gatesville, and she wasn’t alone. Karla Faye Tucker, convicted of murdering Jerry Dean and Deborah Thornton with a pickaxe in 1983, had also gotten the death penalty. The two had actually met back at the jail. To Perillo, Tucker seemed cold, even scary. The 24-year-old Houstonite got into fights, and Perillo remembers thinking her eyes looked “black” when they met.

“I’ll tell you what, I have never seen a more real conversion than with Karla,” Perillo says.

Tucker’s story would become the subject of national debate leading up to her controversial execution. Tucker experienced a religious conversion in prison, and to all the world it seemed genuine. People from former presidential candidate Pat Robertson to then-Pope John Paul II opposed her execution, arguing it wasn’t right to execute her after she had changed so profoundly.

In the meantime, Perillo and Tucker became friends, bonding over their newfound religiosity and creating an almost warm culture behind bars.

Women’s death row was as clinical as any other part of the prison. The women had separate cells. The common space was a white room, benches bolted to the floor. Separated by a mesh divider, there was a work room where the women sewed stuffed dolls for sale. But Perillo and Tucker softened the space, draping afghans over the uncomfortable seating options and placing handmade cloths on the tables.

Reverend Linda Strom, Tucker’s spiritual adviser and a frequent visitor during this time, said the setting was a lot more joyful than she expected: “You could tell that they really cared about each other, and I think freely shared their lives with one another.”

Meanwhile, their numbers grew. A jury sentenced Betty Lou Beets to death in 1985 for killing her husband, Jimmy Don Beets. Frances Newton joined in 1988 after a jury convicted her for the murder of her husband and two children, despite her fervent innocence claims. Perillo leaned into being the matriarch, teaching everyone how to knit and crochet.

The first Christmas that Newton was there, Tucker had crocheted baby dolls for each of the women. Perillo says Newton cried when she opened hers, seeing that Tucker had made her doll Black to match her skin tone. “It was such a sweet thing. I think that’s what got Frances to see that we really cared about her,” Perillo remembers. “We were like a family.”

In 1998, Tucker became the first woman executed in Texas since the Civil War.

Today, Perillo’s been out of prison for six years. But she’s still acclimating. She’s on parole for life, which means regular phone interviews, random urine tests, and prior approval any time she wants to leave the state.

She doesn’t have too many reasons to travel far. Her son Joseph Tise, now 47, lives in the Houston area with his wife and two daughters, ages 16 and 9. Perillo arranged for him to move to Texas when he was six years old, wanting to remove him from the environment she’d grown up in. He lived with friends of Perillo’s who became his legal guardians. Tise told me his relationship with his mother was “atypical” growing up—with quality time meaning missing school to visit her on death row—but she always wanted to be part of his life. It’s important to both of them that she’s a part of her granddaughters’ lives, too.

“To know her, you see that she is not that same person that you meet in the story of her life,” Tise said. “She’s actually changed her life. She wants to be kind to people. She doesn’t hide who she is to anybody.”

Tise couldn’t take his mother in when she was released because of space and logistics, but Perillo had connections she’d made through death row to lean on.

Former prosecutor Shannon FitzPatrick and her son Lewis McCall Bowden have regularly visited the women on death row every month for eleven years. McCall Bowden first reached out to Perillo in 2014, when he was 18 years old and she was at the Lane Murray Unit and had been off of death row for more than a decade. He and FitzPatrick started visiting Perillo—as well as her friends still on the row at the nearby O’Daniel Unit—soon after. Now McCall Bowden refers to Perillo as his “big sis,” even though she’s 40 years his senior.

“The State of Texas makes every inmate seem like the most evil, horrible [person],” FitzPatrick said. “We demonize them, and we don’t see the trauma of people like Pam Perillo.”

When Perillo went up for parole in 2019, FitzPatrick and her family helped pay for an attorney for the hearing. They also let Perillo move in with them when she got out.

Perillo met nearly everyone she holds dear through death row, in one way or another. People like FitzPatrick and McCall Bowden who visited; the women who were there with her; and even the family members of those women on the outside. She still has friends awaiting executions, including Brittany Holberg, Erica Sheppard, and Darlie Routier.

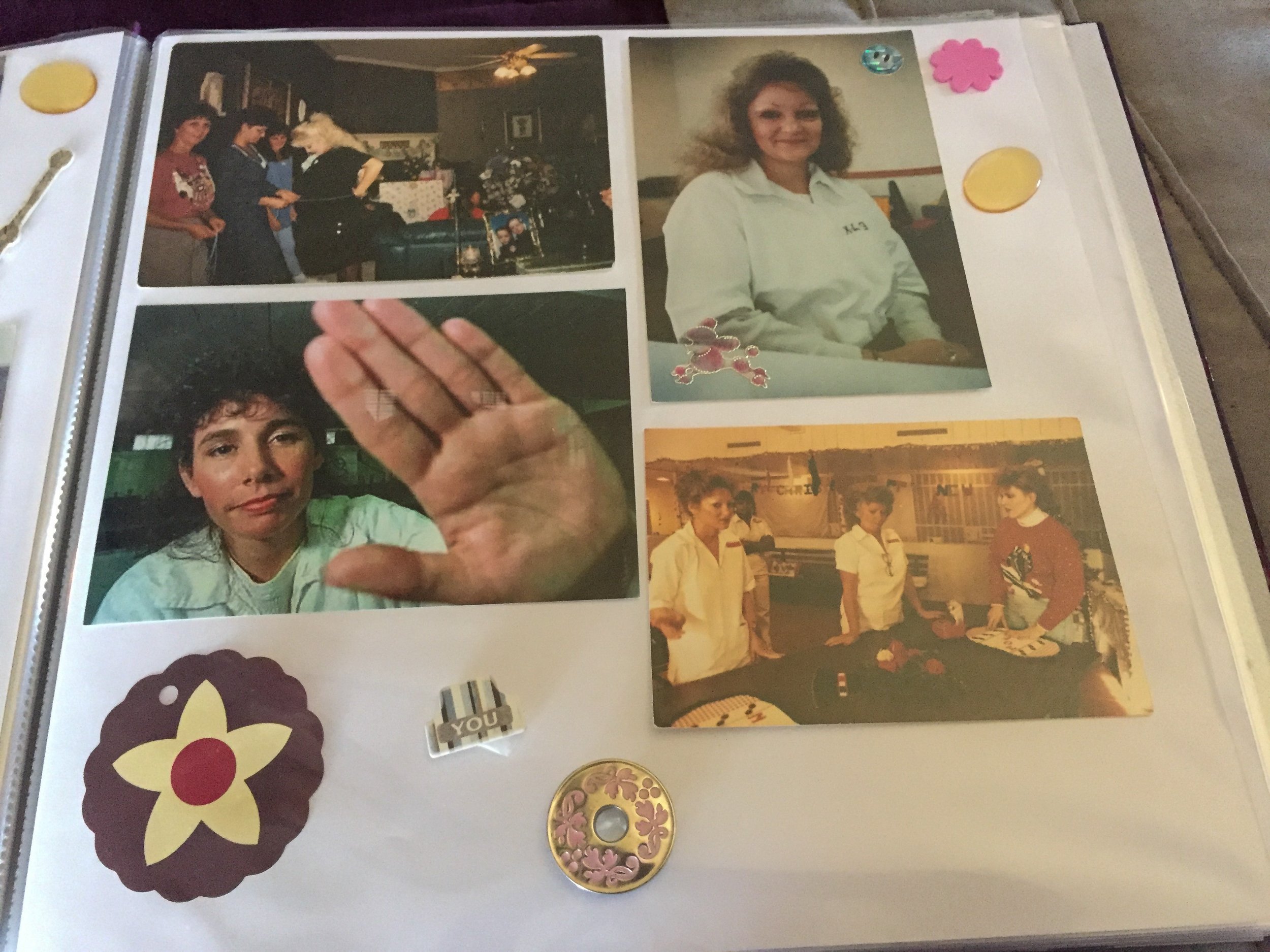

She hasn’t visited those friends inside, though, because she—now a lifelong parolee—has to get approval from the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and the warden in order to schedule a visit. But she looks through the pictures she still has. “We were so close,” she tells me.

Perillo’s friends and advocates told me repeatedly that she’s paid her due for her crimes, but it’s hard to tell if she believes it. Life outside of prison has had its own challenges—a major breakup, housing troubles, and technological progress that’s nearly impossible to keep up with. She continues to tell her story, to confess her crime again and again to anyone willing to listen. When we first met, in line for the bathroom at an event about the death penalty, she told me her name and immediately volunteered that she’d been on death row.

At the August speaking event that I drove her to in Houston, she did ultimately come up with a way to fill the 10 minutes she’d been allotted to speak about herself. She told the crowd of death row advocates, local religious leaders, and a few people just curious about the cause about how much she changed on death row. Before she went to prison, she said, all she cared about was the needle in her arm.

She’d spent years running from any form of community that could help turn around her life—only to find one among the women that Texas had deemed unfit to live.

Credit: Source link