Smoke curled lazily from the kitchen, carrying the sweet weight of brown sugar and spice through the room. An elk and two whitetail deer stared down from the wall, their glass eyes fixed above a Texas flag and a scatter of wooden crosses. Around a circular laminate table, the group of locals bent over a printout titled “The City of Canton: Annual Water Usage vs. Availability Report.” Across from me, behind polarized Ray Bans, a big beard, and a lattice of tattoos, sat a pitmaster named John Borgstedt. Known to locals by his Facebook username, “BBQ and a Prayer,” he was ready to explain how the fight for his livelihood had become inseparable from the fight against the reservoir and the leaders he believes are selling out their own people.

As John’s wife, Virginia Borgstedt, set plates of steaming barbecue chicken and paprika-dusted potato salad on the table, John began to talk. His story reaches back to a childhood scarred by abuse and years in and out of prison before he rebuilt his life through faith and grit. An oilfield explosion later shattered his body and ended his work in the industry. So he set up on Interstate 20 with a cooler and a cutting board on his tailgate, selling barbecue to whoever stopped.

Here in Van Zandt County, which is an hour east of Dallas and stretches across long fenceline miles of pasture and pine, the proposal to build a new reservoir on Grand Saline Creek ignited a fight over land rights, public trust, and the future of rural East Texas. City officials argue the project is necessary to secure Canton’s long-term water supply, but residents say it’s built on inflated population estimates, misleading data, and a failure to follow state transparency laws. Now, landowners, local organizers, and state lawmakers are pushing back, insisting the reservoir threatens generational homes and livelihoods.

The fight over government transparency in Van Zandt County began February 2025 when local realtor Christy Beckham questioned claims that the county jail was overcrowded, leading her to connect with Borgstedt and another local Laurie Wilson, as officials simultaneously pushed for a costly new courthouse while declining a nearly $10 million state restoration grant. The group—suspecting officials may have been manufacturing crises to justify major spending—began to pull public records, attend town meetings, and share their findings online.

The turning point came in March 2025 when a Texas Historical Commission preservation coordinator publicly corrected county officials’ misleading statements—portions of which were later removed from an official meeting video—galvanizing the trio to expose the incident on Facebook. What began as a modest barbecue-and-scripture page evolved into a watchdog platform as Borgstedt posted documents, meeting clips, and maps that brought widespread attention to concerns of local mismanagement and eroding public trust.

The same summer afternoon in August as my visit with Borgstedt, I wound my way through the backroads of Grand Saline, a small town of just over 3,000, the pastures lush and the kudzu heavy with the late summer rains. Along a fenceline, an American flag snapped in the breeze above a cardboard sign, half-swallowed by wildflowers, that read: “Protect Your Land: Stop Canton’s Dam on Saline Creek.”

I pulled into the parking lot of the New Testament Holiness Apostolic Church. Meeting me outside were Cody and Chain Swain, brothers who grew up along the bends and muddy banks of the Grand Saline Creek Basin. Inside the fellowship hall of the small country church, we sat beneath humming fluorescent lights and they told me about the fight Borgstedt had set in motion.

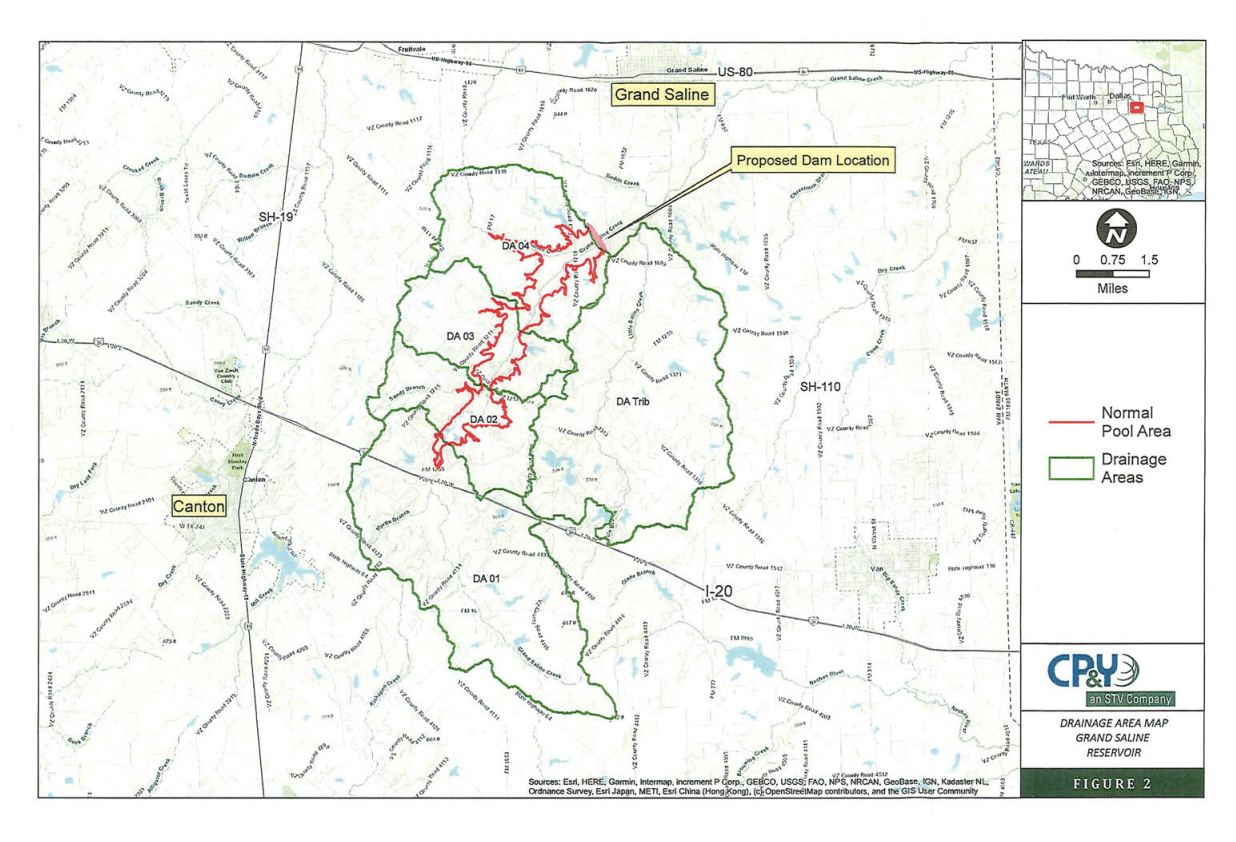

To understand the fight over the water reservoir, one must take the time to understand Van Zandt County’s geography. Canton lies at its hub, with places like Grand Saline, Wills Point, and Ben Wheeler radiating outward, each a small world tied together by county roads and pastureland. Grand Saline, true to its name, rests over the largest and purest salt dome in the United States, where brine-rich earth has shaped both the economy and identity. Morton Salt owns and continues to operate the vast underground rock-salt mine beneath the Grand Saline Salt Dome in the county.

The populations in these towns number only in the hundreds or a few thousand, places where families have lived on the same plots of land for generations. However, there is a force in Canton that has shaped the county’s fate for decades: First Monday, a monthly flea market billed as the “world’s largest flea market.” Once the lifeblood of Canton, First Monday’s decline—ushered in by online marketplaces and commercialization—has fueled suspicions that city leaders began looking to the reservoir as the town’s next salvation, a lake that could lure outsiders, their wallets, and keep Canton afloat.

This all began in 2004. As Canton officials looked ahead to the city’s projected growth, the question of long-term water security came sharply into focus. At a city meeting that year, The mayor and a hired consultant reviewed the Citizen Advisory Committee’s draft comprehensive plan, noting that Van Zandt County’s growth rate was outpacing the city’s and that water would become harder to secure. With just 5.5 square miles within its boundaries, the city discussed a strategy to manage future water demand. This urgency propelled Canton into a series of evaluations and studies, each step tightening the focus on one truth: the city’s future would hinge on a stark choice between just three imperfect options.

The first path was to buy potable and non-potable water from the nearby city of Tyler, a deal dressed in security but bound by an expiration date with no promise of renewal. The second was to raise or dredge Mill Creek Lake, a shallow 237-acre reservoir for which Canton already had water rights. The third path reached the furthest, presenting the Sabine River—which winds for hundreds of miles through pine and prairie before spilling into the Gulf—as the choice to be dammed, a plan that would erase homes and land, submerging family legacies under the banner of “water rights” for a need that remains unproven.

In 2008, a survey was conducted by Gary Burton Engineering at the City of Canton’s request. The firm evaluated five potential reservoir locations. Two were quickly dismissed as unsuitable, while three—the Grand Saline site included—were examined in more detail. Of these, the Grand Saline site was determined to be the worst option: “Three optional dam sites on Grand Saline Creek were investigated and eliminated from further consideration based on excessive relocation costs for gas wells and pipelines,” the report stated.

The City of Canton, based its reservoir plans on the assumption that its population would grow to 34,000 residents by 2065, filling every available space within the city limits and its extraterritorial jurisdiction. (The current population stands at 4,229.) Under that projection, officials claimed the city would face a daily water shortage of 5.78 million gallons. However, Burton’s survey directly contradicted this. Following his survey, Burton pointed out that he reached out to the City of Tyler, a city with a population above 100,000, about 40 miles from Canton, which had agreed to supply Canton with that exact amount. He also contacted the Neches River Authority, which confirmed that at the time there were 25,000 acre feet of unallocated water rights on Lake Palestine, an existing large freshwater reservoir. With these options on the table, Burton’s survey proved, the idea that Canton would run out of water simply wasn’t true.

While this pursuit to build a new reservoir seems harmless at first glance, Chad Swain pulled up a text message from a neighbor sharing with him a newspaper article that ran in 2009 after the survey was discussed. The article published on March 27th 2009, read, “A 237-acre reservoir named Mill Creek Lake already exists southeast of Canton, but it is not considered a major draw for fishing or other recreational pursuits. And while the main focus of the new reservoir is water storage, the lake could be tailored to help draw more water enthusiasts to the area already known for its First Monday Trade Days.” This introduced the suspicion that the reservoir project was not solely for the sake of water needs; there were ulterior motives present in the construction of the lake.

In 2017, the City of Canton commissioned an engineering firm to revisit the idea of a reservoir, this time focusing exclusively on the Grand Saline Creek site, despite Burton’s survey finding evidence that this site was not the most advantageous for the community. They acknowledged the earlier engineering concerns but pressed forward with a more detailed evaluation. The report reiterated the high costs tied to moving pipelines, gas wells, and roadways, while also noting the impact on surrounding farmland and existing utilities. Despite these red flags being confirmed again, the Grand Saline site remained under discussion, its viability framed less by technical promise than by the persistence of officials determined to keep the project alive.

On April 22, 2025, Canton quietly filed its water rights permit application with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), but buried in the paperwork was a telling detail: the city wasn’t claiming its own rights to the Sabine. Instead, it invoked a Certificate of Adjudication held by the Sabine River Authority, SRA, meaning any reservoir built would be under SRA’s control, not Canton’s. For residents who were told the project would secure the city’s independence, the revelation stung. The filing, signed by Mayor Lou Ann Berry on April 15, 2025, also included letters from City Manager Lonny Cluck dated February 25, formally notifying Van Zandt County’s four commissioners and setting the stage for the next phase of the reservoir project.

Per TCEQ regulations, Canton’s Grand Saline Reservoir application should have triggered strict public notice requirements: a notice in the local paper, a plain-language summary posted online, and direct communication so residents could understand the project and weigh in. If the rules had been followed, neighbors should have seen clear notices in paper and online, with a summary of the permit’s purpose and impacts. But in this case, neither the Swain brothers, nor any of their neighbors recall receiving a letter, reading a notice in the paper, or otherwise being alerted to the project.

Some landowners around the creek had seen their property appraisals drop significantly in the year or two before the plan for the reservoir was announced. Wilson pulled up a picture of a map composed of pieces of printer paper taped together with a map of the Grand Saline Creek region pieced together. This map that she had prepared was colored pink and yellow, each region representing a different parcel of land painstakingly pulled from the Van Zandt County Appraisal District. The colors told the story plainly: this was not an isolated case, but a widespread reduction in property values. In some areas, families saw their land devalued by over 30 percent, while others faced cuts as steep as 40 percent—tens of thousands of dollars in lost value, suddenly erased from their most important asset. One parcel, long held in the same family, saw its appraisal fall from nearly $1.2 million to just over $600,000, a 46 percent decrease.

Wilson pointed out a telling pattern: while the value of properties all across the county increased, the Van Zandt County Appraisal District lowered the values of the tracts that sit on the footprint of the proposed reservoir. The contrast deepens the suspicion that these devaluations are not isolated adjustments but a coordinated reshaping of the land market in anticipation of Canton’s project.

In a statement provided by Canton City Manager Lonny Cluck, the city emphasized that the Grand Saline Reservoir project had been publicly discussed and documented since its inception around 2009. “The city has always been transparent and has made all required notifications and filings at the local, regional, and state level in connection with the project,” he said in an email. Cluck stated that notices were mailed to affected landowners at the time and that each stage of planning occurred in compliance with the Texas Open Meetings Act, with filings made at the local, regional, and state levels. He rejected the idea that economic development was a motivation behind the project, saying the city viewed the reservoir solely as a long-term water supply option for Canton and neighboring communities.

Mayor Berry emphasized in a statement to the Observer that the city does not currently face an immediate water shortage and stated that the Grand Saline Reservoir had been considered only as a long-term planning option encouraged by the Texas Water Development Board. Berry expressed personal concern about the declining aquifer levels in the region and the possibility that large-scale water projects in neighboring counties could alter groundwater flow, adding that some wells in the area have already become unstable due to manganese concentrations. She also cited rapid residential development from the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex as an unpredictable factor. “We can control growth but we can’t stop it. Drill Baby Drill seems to be everyone’s motto including us,” Berry said.

City pumpage records filed with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality show that Canton has no water shortage, only a surplus. The city is permitted to draw over a billion gallons annually, yet from 2017 through 2024, it never once used more than 252 million gallons in a year, averaging less than 20 percent of its available capacity. In fact, 2024 marked the lowest usage in nearly a decade at just 192.8 million gallons, and 2025 is on track to fall even lower. Far from running out of water, Canton currently has the ability to supply five times its present population without adding a single new source, records show.

This fight for the community members was often centered in the fellowship hall of the Swain family church, where Chad and Cody sat shoulder to shoulder. They told me how they called a community meeting at their church in late June; the hall overflowed with neighbors angry at the thought of losing their land to the reservoir. Many of those in attendance signed on to a letter that listed the facts, citing the surveys, the population estimates, and detailing what they saw as the immoral nature of the project. At the back of the room sat Borgstedt, silent and watchful behind his sunglasses. He slipped out the door without a word once the meeting was done, later sending a message to the Swain brothers that read: “I’ve seen enough.”

Following the meeting at the Swain family church on June 29, Borgstedt stepped into the role of public chronicler, especially considering the local papers had failed to cover this issue. His Facebook page became a running ledger of what he was uncovering and what officials would not say. He drew on permits, pumpage totals, and charts to show how the city’s claims about a shortage didn’t add up. By July 30, as notice of a commissioners court meeting went out, Borgstedt was posting documents and analysis for residents to see for themselves. As the county held workshops and townhalls, Borgstedt had primed the community with plain-spoken posts that stripped the technical veneer off city documents.

On August 13, the Texas Water Development Board Region D Water Planning Group was scheduled to hold a meeting, with the Grand Saline Reservoir on the agenda, a couple counties over in the town of Pittsburg. The fight over Canton’s reservoir proposal gained some traction. The day before, state Representative Brent Money—a first-term right-wing Republican—sent a formal letter urging the group to remove all mention of the Grand Saline Creek Reservoir from its 2026 Regional Water Management Plan, citing Canton’s surplus water supply projections through 2060, the availability of lower-impact alternatives like groundwater wells and reuse, and the collapse of regional support for the project.

At the meeting, Borgstedt leaned toward the camera he and Beckham had set up in the conference room in Pittsburg. His voice carried as he ensured the people logging onto the livestream could hear him: “Thank you, everybody, for coming into the live. This is such an important message and this is a very big vote. This is something that is definitely going to change, if not influence, the outcome.” Wilson and other local opponents were there as well, carrying eight years’ worth of water reports compiled into spreadsheets and graphs.

The board meeting that morning drew an unusually large and fervent crowd, filling the board’s biggest room despite the stormy weather and it being a midweek workday. Dozens of residents and landowners rose to speak in defense of their homes, some having traveled over an hour to stand with their neighbors. Rep. Money showed up and delivered his own remarks in opposition, as did a staffer from Senator Bob Hall’s office. Their presence underscored the gravity of the moment, signaling that opposition to the project had reached a new level of visibility.

Richard Garza, the Van Zandt County representative to the Region D Water Board, took the floor as the livestream showed Mayor Berry waving to the camera and leaning in to whisper to the man beside him. Garza began plainly: “This situation has turned into a bit of a fiasco, and I don’t feel it was my doing, so I will blame it on the City of Canton.” As he spoke, Berry rose from her chair, moving to the back of the room. Garza then walked the board through the project history—referencing the 2004 meeting, the water studies of 2008 and 2017, and laying out in detail the City of Canton’s misrepresentation of data. What began as a measured presentation of evidence gradually swelled with emotion, Garza’s calm voice giving way to urgency as he spoke of the people around Grand Saline Creek whose homes and land were caught in the balance.

Garza finished with a blistering critique of Canton’s reservoir push, as exclamations of “Amen” and “She’s going to jail” can be heard in the background of the livestream. He argued the city had repeatedly misrepresented data, cycling through engineering firms until they found one that gave them answers they wanted, even though every study referenced the 2008 recommendations. Garza urged the board to take an unprecedented step of opposing Canton’s water rights request, reminding them that while Region D held no legal authority, TCEQ often heeded its recommendations. His voice sharpened as he described the city’s tactics: “This is the lengths the elected officials of the City of Canton will go to in order to get their way… They cannot justify their population. The data and the math are not on their side.” Then, in one of the meeting’s most searing moments, he declared: “I’m tired of them—the City of Canton—molesting the citizens of Van Zandt County.”

At the end of the nearly 4-hour meeting, the people of Van Zandt County secured what many described as a major victory for their land, water, and community. In a unanimous vote, the board members removed the Grand Saline Creek Reservoir from the list of alternative water sources for Canton and issued formal opposition to the TCEQ. For those who had packed the meeting hall, it was validation of their voices. For John Borgstedt and his team, who had spent the last few months gathering documents, speaking with neighbors, and pressing the board for transparency, the decision marked victory.

Since the Region D Water Board meeting, tensions over the proposed Grand Saline reservoir have escalated. On August 15, Borgstedt issued a call to the Van Zandt County attorneys to help pursue the legal removal of Mayor Berry via a state statute that allows a district judge to remove a mayor for official misconduct. Organizers allege city leaders failed to uphold their legal duties and have pledged to provide documents and evidence to support their case. Days after the vote, state Representative Brent Money filed House Bill 162 in the state’s second special legislative session, aimed at limiting eminent domain abuse by prohibiting cities and counties from seizing land outside their jurisdictions and closing loopholes that enable cross-boundary acquisitions. (It didn’t pass.) On August 20, Governor Greg Abbott added a proposal to protect East Texas aquifers to the Special Session Two agenda, marking a significant development in the ongoing fight over water rights.

On October 31, 2025, after months of advocacy and meetings, the Canton City Council voted unanimously to withdraw its application for the Grand Saline Reservoir, formally ending the city’s pursuit of the project after more than a decade of planning. In a media release, Berry stated that shifting political support, renewed public opposition, and changing regional conditions contributed to the council’s decision to let the project “go to the wayside.” Cluck, the city manager, noted that the project initially carried broad municipal and county support, and expressed disappointment that, in the city’s view, the support eroded under political pressure rather than changing water-resource needs.

The city’s withdrawal of the reservoir application may mark a turning point, but no one here is calling the fight finished. The Swain brothers have heard the story of Marvin Nichols, a North Texas aquifer that was similarly contested. They remember stories of men their age, who stood in their town halls, voices thin with age, warning their children to hold the line long after they were gone. That is the inheritance of Cody and Chad Swain, and of Van Zandt County. And though the permit has been pulled; the cardboard signs stay staked in tall grass. Because there, the fight is not a burden but a birthright, passed down like the land from one generation to the next, and the land remains with those who love it long enough to remain.

Credit: Source link